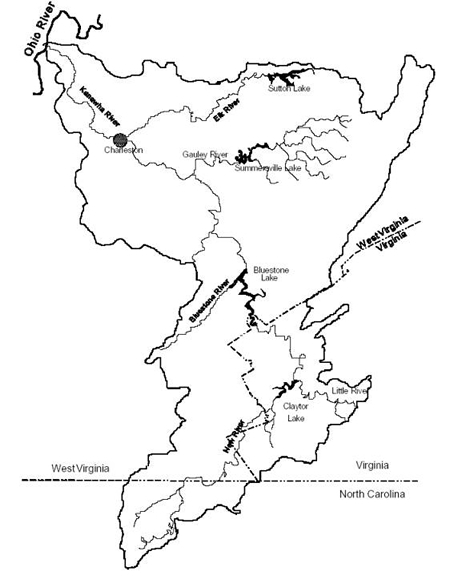

The challenge for the Kanawha River DPS team was to strike a better balance between water quality, lake boating, and white water rafting below Lake Summersville on the Gauley River, a tributary to the Kanawha. The Kanawha drains 12,300 square miles in North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia.

The Kanawha main stem is formed by the junction of the New and Gauley Rivers, and it flows northwest 97 miles before emptying into the Ohio River at Point Pleasant, West Virginia. Other major tributaries are the Greenbriar and the Elk. The Corps is the primary water manager, operating locks and multi-purpose reservoirs at Lakes Summersville (Elk River), Bluestone and Sutton (on the New River). The Appalachian Power Company, which runs the hydropower plants on all three Corps reservoirs, also owns and operates Claytor Lake, on the upper New River. Claytor Lake also supports lake recreation.

The most recent drought started with below-average rainfall in the summer of 1987 and persisted through the fall of 1988. During that drought, releases from Summersville and Sutton were kept high enough through August to meet minimum instream flows established to dilute downstream effluents. By August, there was no longer enough water in the reservoir to support daily-pulsed releases for whitewater rafting or meet minimum instream flow requirements. The restriction of rafting releases to just weekends cost the region millions in tourism revenue.

Releases from Corps reservoirs kept dissolved oxygen levels above 5 mg/l, the state minimum, until August 1988. Then, with the reservoirs running out of water, and temperatures at their highest, the levels of dissolved oxygen dropped, sometimes to less than 3.5 mg/l.

Figure 1: The Kanawha River Basin

Circles of Influence

Circles A and B in the Kanawha included the Huntington District Corps of Engineers (planning and water control), the West Virginia Division of Water Resources, the U.S. Geological Survey, the West Virginia Geological Survey, and representatives from the whitewater outfitters. Circle “C” included natural and water resources departments from all three states, including departments of fisheries, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Trout Unlimited, the Isaak Walton League, regional councils of government, the National Weather Service, Offices of Emergency Service, the North Carolina Regional Council of Governments, the Kanawha Valley Chemical industry, and municipal water suppliers.

The Planning Objectives for the Kanawha River DPS

-

Increase the reliability and value of the Gauley River whitewater rafting experience during drought conditions

-

Increase reliability of the recreational opportunities in-stream and on lakes in the Kanawha River basin during drought

-

Increase the reliability of navigation on the Kanawha River during drought

-

Increase the reliability of hydropower generation in the Kanawha River basin during drought

Changes as a result of this DPS

The study team initially looked at a broad range of tactical and strategic plans (up to and including the construction of additional reservoirs). Almost all but the tactical alternatives were eliminated early in the study process as improbable because of the amount of time necessary to develop solutions and because of environmental concerns. After the shared vision model was developed, the remaining alternatives were screened to see how well they addressed the planning objectives. Planners found that modifications to Claytor Lake, Bluestone and Sutton did not significantly address the planning objectives. In a workshop in the spring of 1993, Circle B team members compared five alternatives for Summersville Lake to the status quo plan.

Plan 1 was to modify the dam at Summersville to allow the summer pool level to be 17 feet higher. Plan 2 called for relaxation of water quality target flows. (A USGS survey showed that BOD loadings had been dramatically reduced since the standards were set.) Plan 3 was to ignore the rules that limited releases from Summersville in the fall (lower limiting rule curve) in order to maintain a preset minimum level of storage. Plan 4 delayed the starting date for water quality releases from June 15 to July 15 unless water samples showed a need for the releases. Plan 5 was to vary the maximum water quality release from Summersville by starting at 500 cfs (instead of 1000 cfs) and increasing through August (the month in 1988 when releases were cut to 400 cfs because of the lower limiting rule curve).

Workshop participants watched as the shared vision model was run to demonstrate the impacts of each alternative during a one- and two- year drought. Measures of performance for each objective were compared. After three hours of model runs, Dr. Richard Punnett, head of the water control section of the Huntington District Corps of Engineers, led a workshop exercise designed to facilitate the transition from individual plan evaluations to the endorsement and implementation of a plan.

The analysis showed that Plans 4 and 5 helped water quality, rafting and lake recreation, while not affecting hydropower or navigation. Plan 2 helped rafters but hurt lake recreation; Plan 3 did just the opposite. Because plans 4 and 5 were not mutually exclusive, the workshop participants agreed that a plan that combined the advantages of both should be used during the next drought.

In August 1993, the Huntington District used the shared vision model and the close collaborative ties it had developed with stakeholders to react to a potential drought. The DPS team agreed to an alternative release strategy consistent with the general form of alternatives 4 and 5. The drought watch was lifted after heavier than normal rainfall. Participants agreed that had the drought continued, these operational changes would have preserved fall water quality and avoided several million dollars loss in West Virginia tourist revenue derived from whitewater rafting.